More on the folklore of beekeeping

I stumbled on an article in the 1914 edition of 'The Bee-keepers Record' about the folklore of bees and beekeeping. Mr J. Smallwood's article describes the myths and folklore of the craft; from classical Greece and Rome, to what was then modern-day Edwardian England. But Smallwood's article focuses on generalities - yet combine it with Mr Woodley's writings about the Berkshire Downs and you get some fascinating insights.

Lovelocks

To meander off beekeeping-folklore topic for a moment, I wish to describe a modern-day folklore phenomena - the lovelock. Have you ever noticed passing a bridge, or railings, festooned with padlocks? Many decorated with love hearts and initials. These weren't hapless cyclists who left them after unchaining their bikes - this was an intential act. A ritual.

The story goes that a school mistress met her lover on a bridge at the spa town of Vrnjacka Banja in Serbia. Subsequently, he was sent to fight in Greece during the First World War. There he fell in love with another woman and never returned. The heartbroken woman never married and died of a broken heart. To save themselves from this fate, local school girls began locking their love on the bridge to avoid the fate.

The lovelock custom generally follows this pattern: the couple decorate the padlock, attach it somewhere meanful, then throw away the key.

Key symbology

In folklore, a key can symbolise many things. Ownership and possession is the first thing that comes to mind, because without the key you cannot access the locked-up property.

Alternatively, the key could symbolise maintaining status quo, so discarding the key might produce a permanent state where nothing changes (so long a no-one finds it). In the case of lovelock, the key is often thrown in the river below the bridge, which makes it almost irretrievable.

Coming back to the symbology of the key, nothing much changes if the owner retains the key. Yet, the potential for change is huge should another take possession of the key.

Beekeeing folklore: tanging the swarm

J. Smallwood writes:

The key: it is interesting to note what an important item of domestic proprietorship it is as connected with bees.

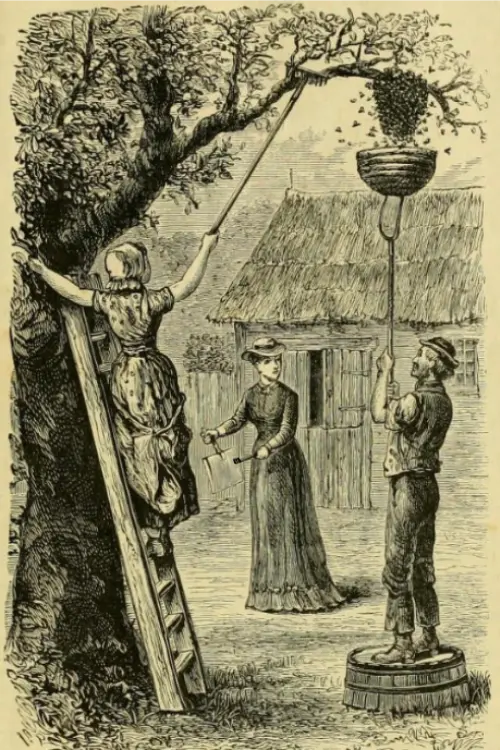

Once a swarm egresses from its hive, the owner would send the alarm by striking the door key against a metal object, thus making a noise. This was known as tanging.

Yet, it is hard to tell if the purpose of making such a raucous sound was to encourage the swarm to settle, or whether it was to alert others. Woodley confirms in 1914 that tanging was done using 'the shovel with a key to make the swarm settle'. Apart from its value as a percussive object, the key symbolises the claiming of ownership over the swarm.

An article in the British Bee Journal recounts a story about the young William Woodley and a swarm:

His careful and well-meaning old guardian insisted on the importance of 'William' keeping himself continually employed, either physically or mentally; and so weeding the garden in the sun was only varied by reading over and over again the Old Testament and the Gospels in the shade.

The tedious monotony of the task was only relieved when a swarm or several swarms issued; then, to the boy's delight, came the banging of tin pots, pans, and all the various means of creating a noise familiar to old-fashioned village bee-life; and when several bee-owners were 'tanging' at the same moment we may imagine the pleasurable excitement aroused by the din!

Beekeeing folklore: telling the bees.

Below, Smallwood describes the cultural consciousness of fairies. This provides an insight into 'telling the bees' of their master's death.

In those bygone days when fairies danced under the greenwood trees, sipped nectar from the flowers, and banqueted in a butterfly, with dew in an acorn cup as beverage. There they dwelt in every nook, and it cannot for a minute be supposed but that between twin creatures, such as the bees and the fairies, there was not some intercourse, and if such were the case equally true it was that they must have been able to talk to each other. This was well known and acknowledged by the mere humans, for the same name "Brownie" called both. But these fairies were so difficult to get in touch with. Scarcely ever were they visible to mortal eye, and yet they were potent for good or evil.

Happy was he who stood well in their favour. His crops were heavy, his cattle thrived and fattened, and in the hen roost the eggs were multi—tudinous. On the contrary, if they were aggrieved with him they racked him with rheumatic pains. There was a blight on his corn, and the milk turned sour ever it reached the churn. Needs must then that there should be an intermediary 'twixt the man and the elf, and in this position were the bees. Therefore all family affairs were whispered to the bee.

Smallwood continues by explaining the custom on the death of the owner of the bees:

The curious thing is that in almost every instance the key of the main door must be taken, and there with a rapping must be made on the side and floorboard of the hive, accompanied at the same time by certain words.

Mr Woodley explains what those certain words are:

"Telling the Bees"— This saying was in Wessex, originally called "waking," or "Waking the Bees." On the death of the owner each hive was adorned with a bit of crape, and notified of its loss by some member of the family tapping it while repeating the words,

"Wake, little brownies, wake. Your master's dead — another you must take." But old customs have nearly died out, and the apiaries that graced the cottage gardens are dying out also in the village of Beedon.

'Telling the bees' seems equally about keeping on good terms with the bees as it is the fairies.

Woodley's contribution to folkore of beekeeping

As I have alluded to in my previous writings about William Woodley, he has left us with an invaluable time capsule - allowing me to fill in the gaps of Smallwood's article. Resultantly, we have a richer picture of the folklore on the Berkshire Downs.

I am writing the biography of William Woodley. Whilst I have one publisher interested, I need to prove I have an audience for my book. If this is the sort of book you would like to see in print, then please consider subscribing to my substack (there is a free option) - it would really help.